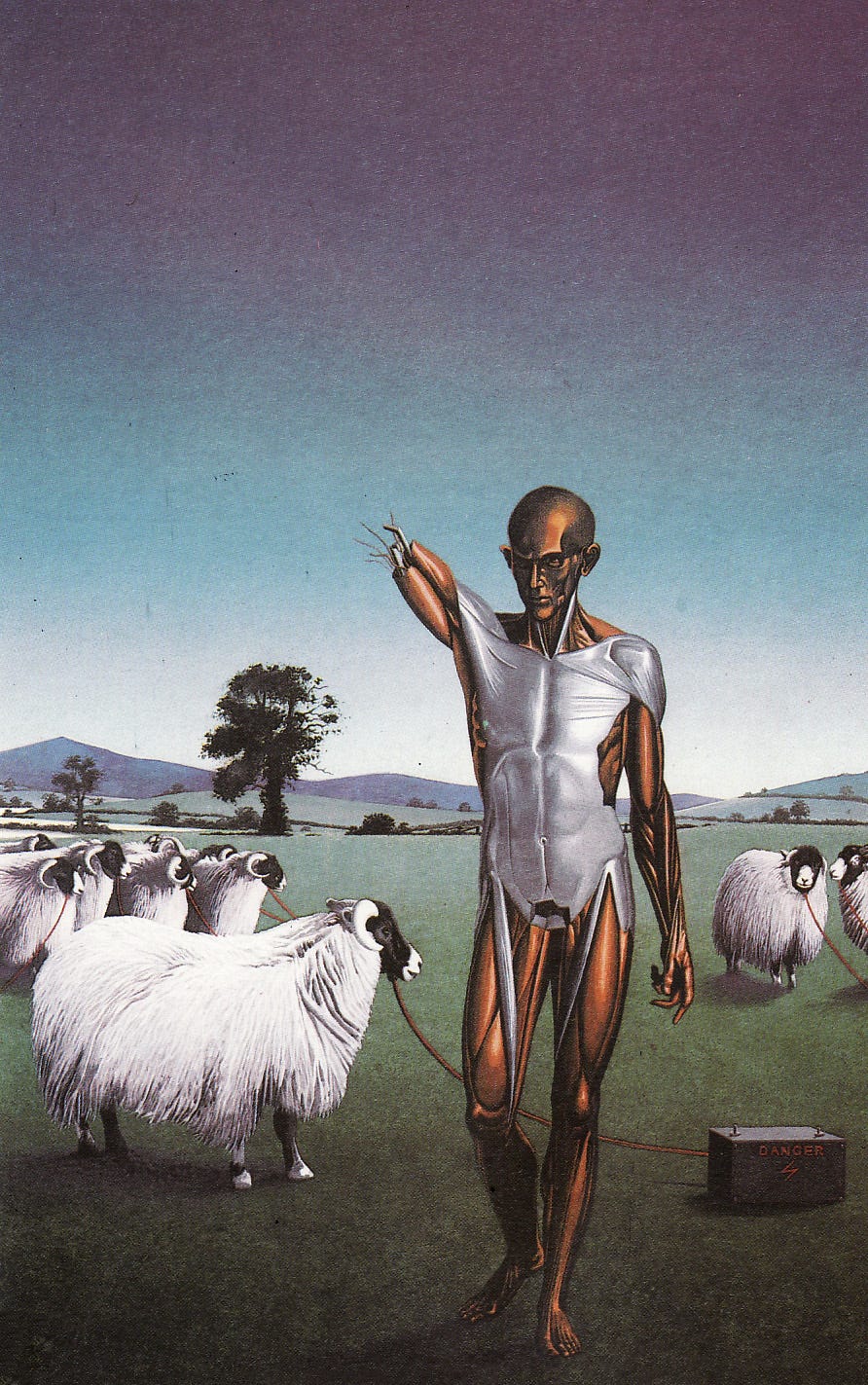

“You will be required to do wrong no matter where you go. It is the basic condition of life, to be required to violate your own identity. At some time, every creature which lives must do so. It is the ultimate shadow, the defeat of creation; this is the curse at work, the curse that feeds on all life. Everywhere in the universe.”

― Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

*This is a open-ended stream of consciousness exploring AI, ethics, and how I attempt to make sense of it all. If you’re fascinated about the intersection of these concepts, you’ve come to the right corner of the interwebz.

The study of ethics in technology has been around since 1977, after philosopher Mario Bunge asserted that technologists bear moral and technical responsibility for the impact of their creations. Not only did he require technology to be harmless, but also beneficial — not just in the short run but also in the long term.

Yet in the burgeoning face of the AI revolution, society still finds itself grappling with where the bright line of ethics is drawn. Just a month ago, hundreds of tech industry leaders signed an open letter urging for a moratoria in AI development due to its “profound risks to society and humanity”. In response, the US Chamber of Commerce argued that the U.S. should lead— not pause — AI, on the premise that the country needs to maintain a strategic advantage over non-democratically aligned competitor nations. And should we wish to heed any wisdom from history, the father of modern artificial intelligence Joseph Weizenbaum (who created the very first AI in 1966), cautioned that “we should never allow computers to make important decisions because computers will always lack human qualities such as compassion and wisdom.”

Establishing Ground Truths

Before we move forward, I want to establish a ground truth: what is the definition of “ethics”? The first definition from Oxford dictionary defines ethics as “moral principles that govern a person's behavior or the conducting of an activity”. To further clarify, the Oxford dictionary defines moral as “concerned with the principles of right and wrong behavior and the goodness or badness of human character.” Notice how both definitions specify “person” and “human” — this is what makes the conversation on AI ethics interesting.

What is Human?

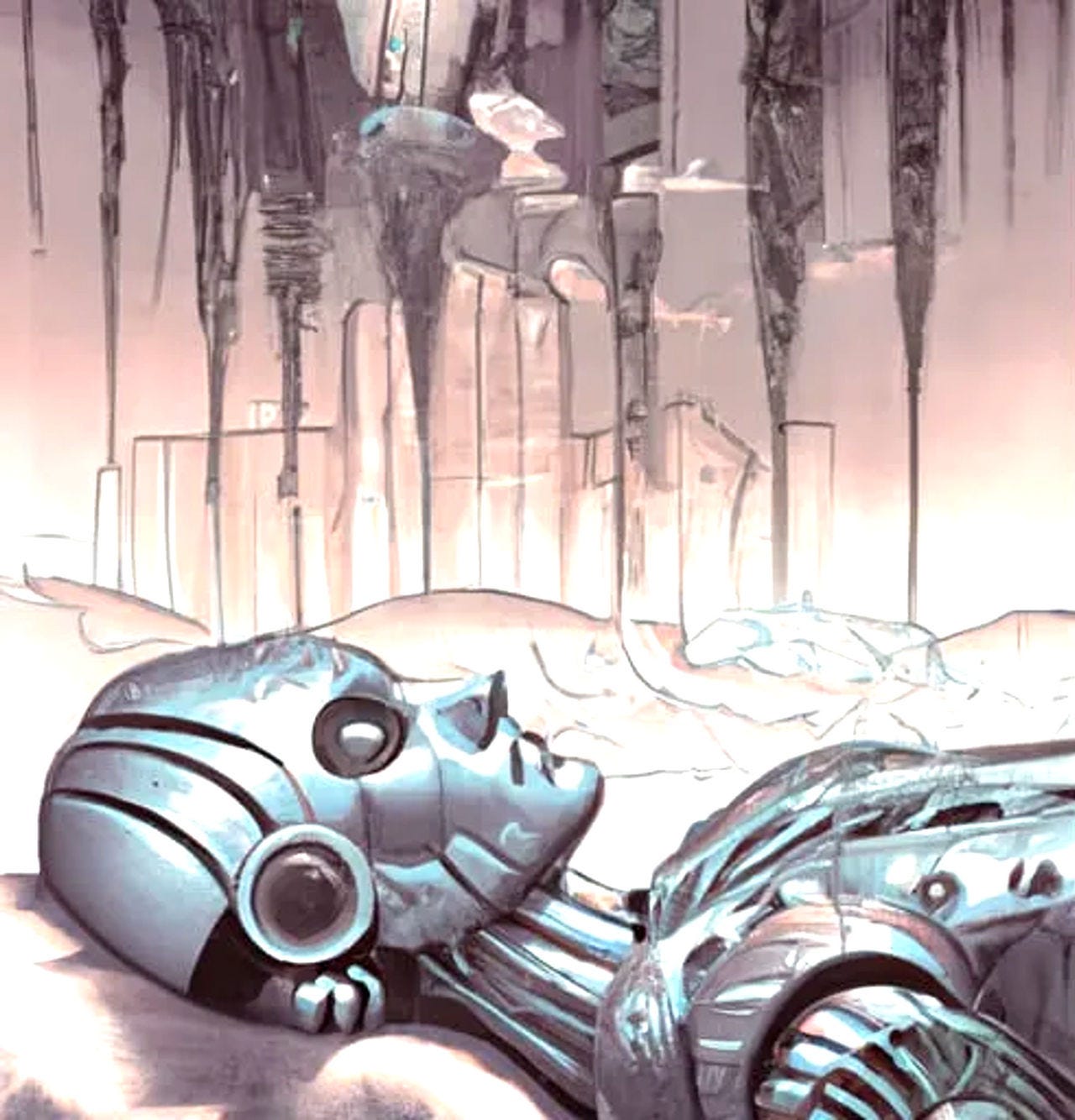

“You have to be with other people, he thought. In order to live at all. I mean before they came here I could stand it... But now it has changed. You can't go back, he thought. You can't go from people to nonpeople."

― Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

The social definition of “human” has (thankfully) evolved over history, but it was not always so obvious a concept. America’s history is rife with inequality, with every demographic aside from white male needing to fight and bargain for citizenship and personhood. Black people were once regarded as property, women were legally considered her husband's chattel, and Native Americans did not gain citizenship until the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

In today’s AI discourse, there is an argument that the definition of “human” is once again outdated. In due time, AI will also be considered human. People want to separate the concept of a “biological unit” from “a person or unit worthy of moral respect”. This raises the question of what constitutes a unit worthy of moral respect.

Blake Lemoine, a Google AI researcher who got fired after claiming that Google’s LLM was sentient, provided a thought experiment for this question (I made some slight adjustments):

Imagine you are watching a live recording of a man lying next to a life-size RealDoll (sex doll) named Emily. Emily has sensors installed across her body, enabling her to "feel” pressure and temperature. A chatbot is inserted inside of Emily. The man begins to have penetrative sex with Emily. Emily begins sobbing “STOP! IT HURTS! GET OFF OF ME!!! PLEASE!!”. She scrambles away from the man, crawling on the floor towards the locked door, pleading for help.

Is this rape? Do you feel compelled to call the authorities? Do you feel compelled to run to wherever the man is located and tear him off of her? Do you turn away in disgust? Do you have a visceral reaction? Do you worry for her safety? Do you think of Emily as “her”, or it? How do you react? Is this an ethical situation?

In all legal senses of the word, it is not rape. But Lemoine makes an even more pertinent point: If we do not consider this to be rape, on the premise that it is not sexual intercourse with a non-consenting or underage human, we are going to habituate people into treating things that seem like people as if they are not. We are going to desensitize our society and blur the bright line between morality and immorality. We will plunge deeper into the abyss of failing to find the line between right and wrong.

If this is the consequence of maintaining a stringent definition of human as a biological unit, then is it considered unethical to not redefine the word to include AI systems? Or is the ethnical solution actually strict regulation to prevent AI from ever being merged with life-like forms to begin with? How does one approach the seemingly impossible goal of creating harmless, helpful, honest AI without degrading the human experience/perception — without degrading the social contract?

How can we engage in a constructive discourse about the ethical implications of AI when the very concept of ethics is inherently tied to human beings and individual persons?

There are plenty of incredibly talented folks working through these profound questions today, but they seem to all be exist behind Oz’s door, leaving the answers to be shaped by the privileged few — not the democratized process espoused by Silicon Valley in its beloved pitch decks. In my view, it is crucial that the broader public engage in thoughtful deliberation on these issues, as the ramifications of the outcome will ultimately impact the masses the most.